Wednesday, July 28, 2010

Relationship: Beauty

All actualities are in relationship. Beauty is an index of relationship. The relationship is beautiful as it is in close interrelation. The more beauty, the greater the positive relation, its harmony and purpose.

Saturday, July 17, 2010

On being process

Thursday, July 15, 2010

Bastien : Folk and Elementary Ideas

Monday, July 12, 2010

Sunday, July 11, 2010

Firstness and Feeling

Saturday, July 10, 2010

The Changing Scientific Reality

Friday, July 9, 2010

Thursday, July 8, 2010

Charles Sanders Peirce

An innovator in many fields — including philosophy of science, epistemology, metaphysics, mathematics, statistics, research methodology, and the design of experiments in astronomy, geophysics, and psychology — Peirce considered himself a logician first and foremost. He made major contributions to logic, but logic for him encompassed much of that which is now called epistemology and philosophy of science. He saw logic as the formal branch of semiotics, of which he is a founder. As early as 1886 he saw that logical operations could be carried out by electrical switching circuits, an idea used decades later to produce digital computers.

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

Products of Process

The brain as a fact is the source of conciousness

becomes

Conciousness is the source of the brain, it produces the structure we know as the brain.

Societies are products of the interaction or relation of actualities.

We know that the brain is made of cells and the cells are made of atoms and the atoms made of energy.

The brain does not create the energy but is a product of it.

Actualities are not just blind plasma. Our experience and consciousness is also a product of actualities. Actualities also possess subjective or experiential dimensions that contribute to societies of experience. The energy brings its experience to the atom, the atom to the cell, the cell to the structures, the structures to the brain.

Does an atom feel? Yes.

Does an atom feel what I feel? No. But we bring into our selves (the society of the human being you are) the atom's experience. And the atom, being part of the society that we are, continues to experience with you as environment. Relationships continue.

So is it with all societies. We are the product of process. That product is not a thing but a process.

Scientific Reductionism

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

René Decarte and Mind/Matter Duality

First, a short description of the work of Decarte...

________________________________________________________________________________

By calling everything into doubt, Descartes laid the foundations of modern philosophy. In Discourse on Method he explains that human beings consist of minds and bodies; that these are totally distinct "substances"; that God exists and that He ensures we can trust the evidence of our senses. Ushering in the "scientific revolution" of Galileo and Newton, Descartes' ideas swept aside ancient and medieval traditions of philosophical methods and investigation.

________________________________________________________________________________

A central issue in process philosophy is around the unity of the stuff of reality. Decarte divided reality into the material and the mental or spiritual. One does not affect the other. We can use matter as so many dead objects, or as John B. Cobb, a process thinker, describes it that all we know in the world as just "matter in motion" and that all relationships are basically physical. Thinking of the world in a Cartesian way allows us to us the material world in a disinterested way.

In Process Philosophy there is a physical and mental reality but they are not divided. Process philosophy does not unite the material and mental (because this is a model that uses objects) but focuses on process/evolution/change. All change so all are "in" process. Actualities (what is real in the world) are in process between the reality they have been to the reality they are drawn to be, between the physical and the mental poles.

Monday, July 5, 2010

Whitehead and Eastern Thought

Mythic Symbols

Mythic symbols are a way of relating or coming into accord with the perceived cosmology. Mathematics and language are symbolic systems. Whitehead uses these systems to help us come into this accord with the cosmos, therefore, one of the best ways of understanding Whitehead is as a mythology.

Alles Vergangliche ist nur eim Gleichnis

But the reference isn't to any thing. It is what is called the void, sunya, and it's called the void because no thought can reach it. So what these symbols are talking about is something that can't be talked about. They have to become transparent. They have to open. What we find then is that the ethnic opens to the elementary. One of our problems - and these are the two great sources, now, of the problem here in Western interpretation of these matters - is the Aristotelian accent on rational thinking and the biblical focus on the ethnic reference to the mythic symbol. These two pin us down to the world of facts and rational cogitation. But from this other standpoint, those are exactly what have to be transcended; they have to be rendered transparent and not opaque. (Joe Campbell)

The Whitehead idea of misplaced concreteness is based on the confusing the symbolic for the referred. We see characteristics of a state and therefore see actualities as states. Symbols are like movies. A movie as reference to actual change is a collection of still images, the collection of discrete images when conjoined are not the change but only point to the process. What can be captured as state (the transitory) is but a reference.

Sunday, July 4, 2010

The Whole as A Whole Becoming

Because all actualities are in the process of becoming, the whole is in the process of becoming. The subjective interactions and experience of all actualities are based on the environment they make for each other. From the subjective point of view of any one actuality, all others are environment. We are environments for each other.

Saturday, July 3, 2010

Perception of the whole

"The many become one and are increased by one." (ANW)

Seeing the world in terms of a whole is an important part of the process philosophy. One way of understanding is a figure/ground. The figure is in the foreground and the ground is in the background. Looking at gestalt (meaning whole) psychology as a companion mode of thinking we see that the figures we perceive as being separate from the ground do not need to be perceived that way. Like a wave is part of the water it arises from, a figure is part of the ground but a part that is in focus (has our attention), has a sense of unity (see last entry) and yet remains part of/in contact/in relationship with its environment. The relationship is unity.

Seen this way all actualities are in relationship and there is no way of moving out of relationship. We are always in contact -- changing, being changed, exchanging experience, forming new societies and engaging novelty.

Friday, July 2, 2010

The Gestalt

Emergence

Emergence is the process of complex pattern formation from simpler rules. It is demonstrated by the perception of the Dog Picture, which depicts a Dalmatian dog sniffing the ground in the shade of overhanging trees. The dog is not recognized by first identifying its parts (feet, ears, nose, tail, etc.), and then inferring the dog from those component parts. Instead, the dog is perceived as a whole, all at once. However, this is a description of what occurs in vision and not an explanation. Gestalt theory does not explain how the percept of a dog emerges.

Reification

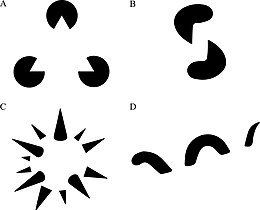

Reification is the constructive or generative aspect of perception, by which the experienced percept contains more explicit spatial information than the sensory stimulus on which it is based.

For instance, a triangle will be perceived in picture A, although no triangle has actually been drawn. In pictures B and D the eye will recognize disparate shapes as "belonging" to a single shape, in C a complete three-dimensional shape is seen, where in actuality no such thing is drawn.

Reification can be explained by progress in the study of illusory contours, which are treated by the visual system as "real" contours.

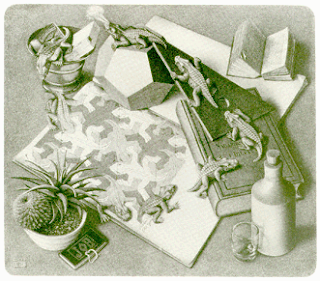

Multistability

Multistability (or multistable perception) is the tendency of ambiguous perceptual experiences to pop back and forth unstably between two or more alternative interpretations. This is seen for example in the Necker cube, and in Rubin's Figure/Vase illusion shown here. Other examples include the 'three-pronged widget' and artist M. C. Escher's artwork and the appearance of flashing marquee lights moving first one direction and then suddenly the other. Again, Gestalt does not explain how images appear multistable, only that they do.

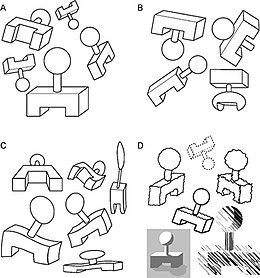

Invariance

Invariance is the property of perception whereby simple geometrical objects are recognized independent of rotation, translation, and scale; as well as several other variations such as elastic deformations, different lighting, and different component features. For example, the objects in A in the figure are all immediately recognized as the same basic shape, which are immediately distinguishable from the forms in B. They are even recognized despite perspective and elastic deformations as in C, and when depicted using different graphic elements as in D. Computational theories of vision, such as those by David Marr, have had more success in explaining how objects are classified.

Emergence, reification, multistability, and invariance are not necessarily separable modules to be modeled individually, but they could be different aspects of a single unified dynamic mechanism.[citation needed]

Prägnanz

The fundamental principle of gestalt perception is the law of prägnanz (German for pithiness) which says that we tend to order our experience in a manner that is regular, orderly, symmetric, and simple. Gestalt psychologists attempt to discover refinements of the law of prägnanz, and this involves writing down laws which hypothetically allow us to predict the interpretation of sensation, what are often called "gestalt laws".[2] These include:

- Law of Closure — The mind may experience elements it does not perceive through sensation, in order to complete a regular figure (that is, to increase regularity).

- Law of Similarity — The mind groups similar elements into collective entities or totalities. This similarity might depend on relationships of form, color, size, or brightness.

- Law of Proximity — Spatial or temporal proximity of elements may induce the mind to perceive a collective or totality.

- Law of Symmetry (Figure ground relationships)— Symmetrical images are perceived collectively, even in spite of distance.

- Law of Continuity — The mind continues visual, auditory, and kinetic patterns.

- Law of Common Fate — Elements with the same moving direction are perceived as a collective or unit.

The Science-Religion Debate

Religion and Science: Finding Their Kindred Spirits (Krista Tippett)

The science-religion “debate” is an abstraction, and a distraction. It isn’t true to the deep nature of science, or of religion, or to the history of interplay between them. These are convictions I’m left with after a cumulative conversation that began a decade ago. And after spending the spring traveling around the country talking about this in theaters packed with scientists and citizens, atheist to devout, I know that others share my sense that our sound-bite friendly, politically-fueled narrative of animosity has outlived its usefulness. There is a science-religion divide — these are two distinct and separate spheres of endeavor. But in the 21st century, we can’t help but hear echoes passing back and forth across that divide and changing the way we understand our humanity, our relationship to each other and the natural world, the contours of the cosmos.

It’s not just the passion and frequency with which mathematicians talk about beauty and physicists talk about mystery that intrigues me. It is also that every time the rest of us log on to our computers in the morning, or every time we eat a meal, we are steeped in the fruits of science. We may not be fluent in the language of science — mathematics — which Galileo called “the language in which the universe is written.” But in the most ordinary moments in our doctors’ offices, certainly in near-ordinary experiences like birth, illness, and death, we receive crash courses in science of many kinds. And we turn simultaneously, without time for debate, to inner territory of morality and meaning, which science has no language for addressing.

Einstein put it this way, helpfully: science is good at describing what is, but it does not describe what should be. That is one way to talk about the role that religious and spiritual practice, our sense of what is right and sacred, plays in human life. And for the record, I don’t believe that spiritual and moral life ceases in the absence of belief in God. Einstein didn’t believe in the personal God of traditional religion. But he did profess a “cosmic religious sense” driven by “inklings” and “wonderings” rather than answers and certainties. Its hallmarks were a reverence for beauty and a sense of wonder that, he acknowledged, he shared with lovers of art and religion.

And it’s worth remembering that, in Einstein’s day, zealous religion appeared less a threat to the future of humanity than science on the loose. He watched chemists and physicists become purveyors of weapons of unprecedented destructive power. He declared, chillingly, that science in his generation was like a razor blade in the hands of a three-year-old. Against this backdrop, he called his contemporary Gandhi — and other figures such as Jesus, Moses, St. Francis of Assisi, and Buddha — “spiritual geniuses.” Einstein soberly observed that these kinds of “geniuses in the art of living” are “more necessary to the sustenance of global human dignity, security and joy than the discovers of objective knowledge.”

It seems clearer and clearer to me that, in the 21st century, genius in the art of living must draw on the best insights of both science and religion, not as argued but as lived. Or, as the Anglican quantum physicist and theologian John Polkinghorne puts it, we come ever more vividly to see how science and religion are both necessary to interpret the “rich, varied and surprising way the world actually is.” I think that the surge of spiritual energy and curiosity of our time is precisely a response to the complexity we know by way of science and technology — not a flight from that, but a turn to sources of discernment to sort, prioritize, make sense.

I was especially intrigued by how the subject of climate change came up when I discussed Einstein’s God in a packed theater in Washington D.C. There the room included scientists from across government agencies — some of them personally religious, some of them not, but all open to engaging the moral aspects of human life that science touches but does not resolve. I heard from people who are working on frontiers of climate change research, including deliberation of how, in a worst-case scenario, we might intervene to change climate, change the weather. This is a cosmos-altering idea on the magnitude of those contemporaries of Einstein who split the atom. But they are deliberating now about the ethical ramifications of this burgeoning possibility, and they are aware of their need of all the resources humanity has to offer for thinking this through.

So what if, as a first step moving forward, we focused less on the competing answers of science and religion, and more on their kindred questions? The question of what it means to be human animates each of these vast fields of endeavor, though they approach and take it up in very different ways. If we just start seeing that, how much more cohesively might we be able to take in the best insights of science and religion, honoring more of the fullness of our humanity, living more gracefully and productively with all that we can know?

In the photo above, physicist Albert Einstein (left, standing behind girl) and theologian Paul Tillich (right, standing in front wearing glasses) at a conference in Davos, Switzerland on March 18, 1928. (Courtesy of Image Archive ETH-Bibliothek, Zurich)

Divided Road Ahead: Spiritual but not religious

“I think in a way that kind of cliche ‘spiritual but not religious,’ which apparently is a thing more and more people say to describe themselves, is in a way an attempt to reconcile in some cases with science. In other words…if I say I believe in this highly anthropomorphic God, if I’m religious and too old-fashioned in a sense, or buy into specific claims of revelation, that might not sit well with the modern scientific intelligence.”

—Robert Wright, author of The Evolution of God (February 2, 2010)

Is the illusion of the duality of human existence something that makes us spiritual but not religious? One of the strengths of Whitehead's Process Philosophy is the unity of reality. There is one reality and therefore we come to all things in relation, it is not an or but an and.

Thursday, July 1, 2010

How alive do we want to be?

What does process theology say about the spread of oil in the Gulf of Mexico? (John B. Cobb)

The question for this FAQ is different. It is about the interpretation of this event and the implications drawn from it.

As a theologian two biblical passages strike me with special force. One of them is found in Deuteronomy, and I will quote Deut. 30:19-20a. “I call heaven and earth to witness against you this day, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and curse: therefore choose life, that you and your descendants may live, loving the Lord your God, obeying his voice and cleaving to him. . .”

The second is found in Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 2:24. “No one can serve two masters; for either he will hate the one, and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and wealth.”

If we put these two verses together the message is clear. To serve God is to live. To serve wealth is to choose death. Of course, through much of history it has been common to spiritualize this teaching about life and death. Its concrete historical meaning has been less clear. But today that unclarity has ended. For us collectively to continue to serve wealth is to bring about more and more death.

There is, further, no doubt that the choice of serving wealth is deeply entrenched in our culture. The world is organized for the purpose of increasing material wealth. “Progress” means increasing per capita GNP (Or GDP). Even now when we see the consequences of this choice in one vivid instance, there is little discussion of changing masters. Most of the talk is how to continue to exploit deep sea deposits of oil with less risk of accidents. I have read the argument that the risk of deep sea drilling should lead us to focus on tar sands as our source of oil. Others argue for massive development of nuclear energy. This is simply a debate about which dangerous method to use to increase our energy supply and support a growing economy. There is also some talk of shifting to sustainable forms of energy, and for this we can be grateful. That could slow the move toward death.

But what would be required to change masters, to choose life? To serve God would mean to aim at the well being of God’s creation inclusively. The one nation that has come closest to making this choice is not a theistic one. It is the Buddhist kingdom of Bhutan. It aims at the gross national happiness! Although this could be understood in a purely anthropocentric sense, the Bhutanese know that human happiness is bound up with the health of the natural environment. To whatever extent they are serious about their commitment, they will judge economic activity by its contribution to the well being of the whole community. That, in turn, will mean that they will not sacrifice the well being of their children and grandchildren for present gratification of desires. Only sustainable economic activities will be allowed.

That the Bhutanese have chosen life shows that they take their Buddhist beliefs with far greater seriousness than we take our Christian ones. Very few Christian voices have been raised in a realistic call for overturning the economism that so clearly reigns in our societies and national and international affairs in favor of serving God. Given the clarity of Jesus’ teaching, this is profoundly disappointing. I hope that before I die I will hear a sermon on this topic.

Christians have not always accepted the organization of society in the service of wealth. Until modern times and especially the industrial revolution they understood how the desire for gaining or retaining wealth damaged the spirit of individuals. In opposing the service of wealth, Christians today have most of the tradition on their side. But this feature of Christian teaching has faded in the past two centuries as we have learned that industrial organization of labor and substitution of fossil fuels for human labor greatly increases the goods available to society as a whole.

Now, what about process theologians? I like to think that we have been more articulate and impassioned in directing humanity toward life than most others. We certainly should have been. Whereas in the case of most theologies, their philosophical commitments are a drag on their biblical ones, in our case, they reinforce the biblical message. The difference I have in mind is that process thought gives a large place to nature and locates human beings within it, whereas the dominant philosophies of the modern world are radically anthropocentric.

The official teaching of the churches has greatly improved, and I think that process thinkers have contributed to this improvement. Charles Birch, a Whiteheadian biologist, gave important leadership to the World Council of Churches. Herman Daly, a Christian Whiteheadian economist, has long been the leader among the fringe group of economists who take ecology seriously. A few of us process theologians also participated in the theological and philosophical discussions about priorities from the early seventies. When I was awakened, I gradually learned that even before the cultural awakening, there had been concern about ecological matters on the part of the previous generation of process thinkers. Charles Hartshorne deserves honoring on this point, although its role in his writings is disappointingly small.

In any case, process theology as a whole should stand unequivocally on the principle that the economy should be in the service of the created order, that the created order should not be exploited for the sake of the economy. This message is simple, but getting serious attention to it is not easy even in the church. Practically speaking it would mean determining how much energy (and other resources) can be produced without damage to the created order and then shaping an economy that functions within those limits. Of course, in shaping that economy the focus should be on meeting the real needs of all. This does not exclude a role for the untrammeled market or the entrepreneur or the corporation. It does not require radical egalitarianism. But the society we need cannot place the freedom of the market or of entrepreneurs or of corporations above the needs of human beings and other creatures. Jesus reminded us that the Sabbath is made for human beings, not human beings for the Sabbath. Similarly markets and entrepreneurs and corporations should be in the service of human beings – not demanding their sacrifices.

In terms of the contribution of process theology I have emphasized locating humanity within nature. As we think about the organization of the human economy, process thought has another advantage. Most modern philosophy is radically individualistic. This individualism is taken for granted in the dominant economic theory. For process thought, our relations with one another are a central part of who we are. We become persons in community. We are benefited far more by the wellbeing of the community in which we live than by our competitive ranking within society. This provides us with a different way of approaching economic issues.

May we choose life before it is too late!

Whitehead and Anthropology by John B. Cobb, Jr.

John B. Cobb, Jr., Ph.D. is Professor of Theology Emeritus at the Claremont School of Theology, Claremont, California, and Co-Director of the Center for Process Studies there. His many books currently in print include: Reclaiming the Church (1997); with Herman Daly, For the Common Good; Becoming a Thinking Christian (1993); Sustainability (1992); Can Christ Become Good News Again? (1991); ed. with Christopher Ives, The Emptying God: a Buddhist-Jewish-Christian Conversation (1990); with Charles Birch, The Liberation of Life; and with David Griffin, Process Theology: An Introductory Exposition (1977). He is a retired minister in the United Methodist Church. His email address is cobbj@cgu.edu.. This paper was written in February, 1990.

The encounter with Alfred North Whitehead in my student days was a revelatory event. It proved determinative of my theological career. I learned through him, gradually, a way of perceiving and thinking that was markedly different from what I found elsewhere. Once I entered into it, I could not leave it, even if I wanted to. I simply see the world differently because of his influence upon me.

What initially attracted me to Whitehead was the relation of his thought to my personal crisis of faith. That centered around the reality of God. My teacher, Charles Hartshorne, dealt with that question in a rational way that spoke directly to the questions I was asking. Such rational speech about God was rare in the Protestant theological climate of the time, and it is rare today. I saw that my problem was that what I understood by "God" did not fit with the "modern mind" into which my education was socializing me. To believe in God in a realistic way required that one dispute the nature of reality with modernity. Of course, it also required rethinking what one could mean by "God."

Through Hartshorne I was introduced to Whitehead's writings. I found in him one who did dispute the nature of reality with modernity in rich detail and with powerful analysis. I saw that a quite new, but deeply moving, understanding of God fitted well with Whitehead's postmodern vision of reality. It was this, above all, that drew me to him.

I would not recount my story if it were mine alone. While the great majority of Protestant theologians turned to Barth and other Neoorthodox thinkers, a few of us felt the need to deal directly with the question of God's reality, in a way that could not avoid philosophical issues. Some of us found decisive help in Whitehead, and, out of that, what has been called in later decades "process theology," was born. Process theology was, therefore, chiefly associated with its doctrine of God and secondarily with its interest in ontology and cosmology. One of the main criticisms directed against it was that it had no anthropology.

Of course, that was not quite true. We found some interesting comments on the nature of human beings and history in Whitehead, and there were obvious anthropological implications of his theology and his cosmology. But still, it was true enough. Most of us who were drawn to Whitehead because of his theology and cosmology, looked elsewhere for our anthropology. The thinker who was most influential in shaping our anthropology was Reinhold Niebuhr, whose Nature and Destiny of Man informed a whole generation of thinking in the United States. One could almost say that the anthropology of process theologians was that of Niebuhr, but not quite, because there were others who found their anthropology in Heidegger or in Sartre.

There can be no doubt that this dependence on others for a rich doctrine of human beings was a weakness of process theology. In some instances, process theologians worked hard to show the integrity of their unification of Whitehead's cosmology or theology with the anthropology they advocated. Schubert Ogden made a convincing case for the complementarity of the theology of Hartshorne and the anthropology of Rudolf Bultmann. David Griffin argued for the integrity of the more common merger of Whitehead with Reinhold Niebuhr. These programs were significant and fruitful. But in a context in which anthropological issues and approaches were becoming increasingly dominant, the fact that process theology seemed to have nothing of its own to contribute, appeared to many to justify their neglecting it.

Over the years this situation has changed. Whiteheadians are finding in Whitehead's cosmology significant anthropological implications that can be developed on their own, or in critical interaction with the anthropological work of others. It is my belief that, in the long run, Whitehead's contributions to anthropology will prove just as significant as his contributions to theology and cosmology. But before attempting to identify some of these contributions, I need to introduce you to the basic insights of Whitehead's metaphysics.

II

When we think of the ordinary things that make up the world, we are most likely to give such examples as sticks and stones and tables and chairs. These have played a large role in the history of philosophy. Their importance is not to be doubted, and that importance is highlighted in our ordinary language. Objects of this sort often constitute the subjects of our sentences. If we think a bit more about the world, we are likely to recognize that in addition to objects like these there are also subjects like ourselves.

About objects we utter simple propositions such as "The stone is gray." This suggests that there is an object, the stone, in which there inheres the attribute, gray. The stone seems to remain the same stone even if someone paints it green. It seems that we can distinguish the unchanging stone from the changing attributes. This leads us to distinguish the stone as a substance, that is, at that which figuratively "stands under" the changing qualities, properties, or attributes. We can then ask whether the substance has some unchanging or essential qualities, properties, or attributes as well as the primary ones. We may then distinguish these as primary qualities from the secondary ones.

Similar questions can be asked about ourselves as subjects. It is natural for me to think of myself as the underlying or substantial reality which acts and is acted upon. Our ordinary language encourages us to think this way. I speak of how I felt yesterday and what I am doing today in a way that appears to imply that the same "I" suffers and acts in different ways at different times. Many of my qualities, properties, or attributes change during the course of my life, but it seems that this does not mean that I cease to be self-identically myself. It is then natural to ask for the essential or primary characteristics that constitute me as a subject.

Out of reflection such as this emerges philosophy of the Cartesian type. And although everyone wants to overcome Descartes, language seems to bring us back again and again to Cartesian-type thinking. We treat the world as made up of two kinds of substance, material and mental, and we distinguish these substances from their changing characteristics and from their changing relationships with one another.

I will not rehearse the history of modern philosophy in which the Cartesian notion of substance became more and more difficult to maintain. Whitehead rejects it, and in that he is certainly not alone or even unusual. What is unusual is that Whitehead develops an alternative conceptuality into a full-fledged cosmology and metaphysics.

Whitehead points out that not all of our sentences are about objects and subjects. We also speak about events, actions, occurrences and experiences. I can speak of a conversation I held yesterday or of eating breakfast this morning. Conversations and eating meals are neither subjects nor objects. Everyone knows this. But most modern philosophers have supposed that when we analyze these events fully, we can explain them in terms of the activities of subjects or the motions of objects. Most modern thought about the physical world has assumed something like the metaphysics of Greek atomism, namely, that there are irreducible bits of matter that change only in relative position.

Whitehead is one of the voices raised in favor of the alternative theory. This is that when physical things are fully analyzed they turn out to be patterns of events. This means that the things of which the world is made up are not either subjects or objects but happenings, occurrences, actions, or experiences. We are not to think of subjects or objects that act or are acted upon but of activities as such. In our own case, we are not to think of a self that first exists and then experiences and acts but rather of experiences and acts as the fundamental reality.

Whitehead was a mathematical physicist, and there can be little doubt that the breakdown of materialistic and substantialistic categories in physics played a large role in persuading him to look elsewhere for what is most real. But, of course, there have been purely philosophical reasons for making this metaphysical change as well. In quite different ways, the names of Hume and Hegel suggest some of these reasons to those familiar with the history of modern philosophy.

Thus far I am simply locating Whitehead in one tradition of modern philosophy. From here on I will be speaking of distinctive ways in which he has developed that tradition.

First, Whitehead sees both human experiences and the quanta of energy discerned through the analysis of atoms as instances of one and the same metaphysical type. Both are events or occurrences. Whitehead calls them "actual occasions." There are great differences between them, but both exemplify a common basic structure.

Second, this common basic structure is that of the many becoming one. It is a process of concrescence, that is, a process in which a new concrete actuality emerges from the diverse actual occasions that make up its world. But stating matters in this abstract way will not help you much to understand this quite radical point.

Let us think instead about how a moment of human experience comes into being. It grows in large part out of antecedent experiences. For example, as one listens to the last note in a phrase of music, the hearing of the preceding notes still reverberates. Otherwise, one would not hear the phrase at all. That means that the earlier experiences are still present in the later one. They comprise much of the content of that later experience. But, of course, they don't exhaust it. There is a new note sounding in the new experience. That means that mediated through the air and through the nervous system, events in the external world, perhaps someone playing a piano in the room, also become part of the new experience.

Although these may be the dominant parts of the world of the new occasion of experience, they do not exhaust it. Usually there are visual and tactile elements in the experience as well. There are memories of earlier events and anticipations of future ones. The condition of the liver and the kidneys has its effect on the experience as well. And, through these and other aspects of the immediate environment, more remote influences are also at work. Thus the whole world flows into the present, to a large extent making it what it is.

What is most important to grasp here is that there is not first an occasion of experience that then relates to its past. Instead, the occasion only comes into being as these past events inform it. The new event includes the past events, and it has no existence at all apart from this inclusion.

Of course, not every feature of all those past events is included. On the contrary, most of what has happened in the past is lost. Even when we are dealing with the immediately preceding moment, we realize that what is still alive now is less than its totality. With respect to more remote events, most of the richness is lost.

The activity of concrescence is not simply the inclusion of aspects of the past. There is also supplementation. In our example of listening to the final note in a musical phrase, there is not simply the numerical adding of the notes to make up the phrase. The moment in which the final note is heard is one in which the phrase as a whole attains a unity and completeness that was not present in any of the antecedent moments or in the final note taken by itself. Each occasion of experience not only receives from the past. It also interprets the past and evaluates the past. It relates elements of the past to one another in creative ways. In this process there is a transcending of the past and a determination of just how that past will be integrated and transmitted to the future. Whitehead calls this a decision. Each occasion of human experience makes a decision about itself in view of the past that it includes and the future that it anticipates.

This is an example of how the many become one. I have said that every actual occasion, including quanta of energy, are also examples of many becoming one. Obviously they are not listening to music. But they are also ways in which their worlds express themselves creatively in new happenings. The formal pattern is the same, although the qualitative character is extremely different. This means that even a quantum of energy is, for Whitehead, an occasion of experience. That is, it is a way in which the world is actively appropriated at a particular locus in space time. Of course, this does not mean that quanta have sense experience or consciousness, but even in human beings, these are not fundamental. One is never conscious of more than a tiny part of the whole of one's experience.

III

The fact that Whitehead emphasized what is common to all actual occasions, human and not, was a major reason for skepticism about his contribution to anthropology. And as I have already stated, Whitehead's personal contribution to anthropological thinking was indeed limited. Yet those of us with strong anthropological interests who have followed Whitehead have found again and again that the acceptance of his general scheme of thought has important implications for how we think about human beings.

Whitehead's project to find, in occasions of human experience, patterns or structures that can be generalized, presupposes and implies the view that human beings are wholly, and without remainder, part of the natural world. Perhaps many people would verbally agree. But if one studies the anthropologies that have appeared in the various disciplines, one finds that this agreement has little affect on what transpires. The categories in which the human condition is discussed are quite different from those that function when other topics are in view. Even the human body is usually largely invisible in the discussion of human phenomena. Most discussions of psychology ignore physiology, and most discussions of physiology ignore psychology. Most discussions of economics ignore the actual character of physical reality, and most discussions in the physical sciences ignore the existence of human beings and their impact in the physical world. The divide is very deep indeed.

This is particularly surprising in a Darwinian age. Most of the practitioners of most of these disciplines acknowledge that human beings have evolved from prehuman ancestors. Most of them deny that there was a radical break at any point. Yet this acknowledgment has no effect on their intellectual and scholarly activities.

There are exceptions. For example, some scientists do attempt to throw light on human behavior through the study of other creatures. Recently some of these, calling themselves sociobiologists, have attracted considerable attention. But, on the whole, their approach reinforces the resistance to the practical acknowledgment of continuity by others. It follows the old pattern of a discredited scientism in being reductionistic. Many students of humanity are willing for reductionism to have its way in the rest of the world, but most are determined to adopt a quite different approach in the study of human beings.

Basically, the old choices of dualism, materialism, and idealism still hold sway in practice, even when they are eschewed in theory. In the organization of knowledge in general, dualism is dominant. In the study of human beings the practical attitude is that of idealism, namely, that the physical sciences ultimately tell us nothing about the way the human world really is. Hence they can be safely ignored. In the natural sciences the practical attitude is reductive materialism. In this context, to be serious about locating human beings within nature, without any tincture of reductionism, is a quite distinctive project, even if the effort is not unique to Whitehead.

For Whitehead, as for Teilhard de Chardin, to affirm that human beings are part of nature is also to affirm that nature is much richer than Western thought has usually acknowledged. If we are truly to overcome dualism, we must recognize that every natural entity resembles human experience in some way, for there is nothing of which we can be more sure than that there are human experiences in the world. The task is not to ask whether there is such resemblance, but rather, what are the similarities? One must find ways to test the hypotheses about nature that arise from this approach. In this way, one builds up the scheme of concepts that are proposed as universally valid.

But the movement of thought must proceed in the opposite way as well. Although all things exemplify some structure in common, they also differ marvelously from one another. These differences cannot be derived from the categories. A universe exemplifying the categories could still be very different from this one. Indeed, it once was. Whitehead's interest, as a cosmologist, is in the contingent features of this universe, with its enormous variety of inorganic and organic structures. Above all, what is fascinating is the emergence of the wonders of organization of the human body and the emergence in its brain of distinctively human experience. There is some commonality between a quantum of energy and a human experience. But once that is recognized, the challenge is to bridge the chasm that separates them.

It is my experience that thinking of human beings in this way heightens the wonder. So many things are simply taken for granted in the humanistic disciplines that are in fact truly astonishing! Life itself is still radically mysterious, as is every step of the evolutionary process. The more we know about it, the more amazing it appears. Some years ago Jacques Monod, in his well known book, Chance and Necessity, seemed to argue that the discovery of DNA had dispelled the last mystery. Recently, Fred Hoyle has written, in Evolution from Space, that the conjunction of circumstances required for the emergence of life is so improbable, that it is statistically virtually impossible that life could have originated on this planet. It must have come from elsewhere. Other scientists have invoked an "anthropic principle" to explain the whole succession of improbabilities apart from which human life could not have emerged. My point here is not to take sides with any of these speculations, but only to indicate that the initial insistence on locating humanity fully within nature, heightens the marvel of creation that is too often lost when we stay within our dualistic compartments.

Consider a very simple example. Suppose I recognize the cup on my desk as the one from which I drank earlier today. This seems like such an elementary example of human cognition that it arouses no surprise or puzzlement. That it is far more complex than it first seems, can be shown by the phenomenologist's analysis. But suppose we undertake a natural analysis, that is, try to work through all the physical and psychic activities that are involved, first in seeing the cup at all, and then in recognizing it. Consider, above all, the activity of what Whitehead calls "the final percipient occasion", i.e., the present occasion of human experience, in integrating its present visual experience, with all the complex interpretation involved therein, with previous experiences. The whole process boggles the mind. It is fortunate that we can see and think without understanding how seeing and thinking are possible!

I am belaboring this point to stress that being a thoroughgoing naturalist has nothing to do with being a reductionist. On the contrary, authentic naturalism puts an end, once and for all, to any possibility of reductionism. It makes almost inescapable an awareness of some mysterious working in the whole process. Whitehead spoke of this as God. In Whitehead's view, God is a factor in every event whatsoever. There can be no intervention; for the notion of "intervention" presupposes a sphere from which God is absent. For Whitehead, there is no such sphere. To be a naturalist, in the Whiteheadian sense, is to affirm a sacramental universe. This awareness of God's presence in oneself, in other people, and in the whole of creation, is an essential part of a Whiteheadian anthropology.

IV

A second major effect on anthropology that results from adopting Whitehead's vision is a shift away from the kind of individualism that the Enlightenment fixed in modern common sense. We think not only of objects as self-contained in particular regions of space and related to one another only externally, but we think of human selves that way, too. I am here and you are there. And we suppose that my influence on you and your influence on me are secondary and external to our independent identities. Whitehead forces us to reject this way of thinking.

My own work in this regard has been especially in economics. There it is very clear that Homo economicus is individualistically conceived. Of course, all economists know that their model of the human being is abstracted from the fullness of human existence. People are also Homo religiosus, for example. But economists rarely comment on the fact that Homo economicus is abstracted from the relational and communal character of actual human beings.

If one views human beings, with Whitehead, as fundamentally social beings, that is, as having their being and their value in their relations with one another and with the remainder of the world, then the abstraction of the individual producer and consumer from this communal being can no longer be accepted. It distorts the whole of modern economic thinking. Where public policy has been most influenced by this theory, as in the United States and in many development programs in the Third World, the results have been immensely destructive of human community.

I have written a book with a Whiteheadian economist, Herman Daly. It is called For the Common Good. In it we argue that for purposes of developing economic theory, human beings should be considered persons-in-community. The effort to improve the economic lot of human beings will then ordinarily be seen as improving the health of their communities rather than as increasing per capita consumption.

The only modern economic theory that I discovered that supported this shift was that of nineteenth century German Catholic economists and of some Papal encyclicals influenced by them. This has led me to acknowledge that Catholic thought has always exercised a healthy check on the individualism that I have rejected as a Whiteheadian. The only limitation of this Catholic tradition which I now believe to be important is that the pattern of relations it emphasized did not include relations to the land and to the other creatures with which we share it.

V

There are other, more specific and immediately practical, consequences of Whitehead's naturalism. Ethics must be changed. Both Christian ethics and Enlightenment ethics assumed that duties are owed only to other human beings, that only human beings are ends in themselves. This is, obviously, based on a dualistic view of the relation between human beings and animals. For a Whiteheadian it is more natural and correct to speak of the relation as between human beings and "other" animals; for humanity is one species of animals. Given that understanding, there can be no question but that animals are deserving of moral consideration.

The dualistic habit of mind that has excluded treatment of animals from Christian ethics, has also led to strange results among those who have become concerned about this treatment. The tendency has been to move the line that separates the sphere of ethical relevance from that of no relevance, not to abolish it. Thus Schweitzer removed the line between human beings and other living things, and drew a new one between living and non-living beings. In general he applied to the relations of human beings to all other living things, the principles that had their initial application among human beings. He opposed discriminating among living things in terms of more or less value, although in practice he was forced to engage in such discrimination. The same pattern exists among philosophers who support animal rights today. The typical question is where to draw the line.

From a Whiteheadian perspective, this effort to draw a line is a continuation of untenable dualistic habits of mind. One might draw thousands of lines, for every difference makes a difference, but drawing one line distorts our thinking. We take many of the entities on the nearer side too seriously, and many of the entities on the farther side too lightly.

Actually, Whiteheadian thinking supports what people in a common sense way are likely to think anyway. Most people are more concerned about killing porpoises than killing tuna. This distinction is a matter of law, at least in the United States. Similarly, we are more disturbed about the suffering of a chimpanzee than that of a chicken. A mouse has greater claim on our ethical consideration than does a bacterium. And so it goes. They are all alive, but we see more intrinsic value in some than in others.

Critics argue that these distinctions are sentimental and without basis. They say that we value animals according to their attractive appearance or according to their resemblance to ourselves, that a rational approach would be to respect them all equally, because they are all alive, or all sentient, or because all have interests, or according to some other fixed criterion. Whiteheadians disagree. No doubt sentimental factors enter into our actual judgments, and they should be discounted, but there are real and important differences. Value lies in the subjectivity of occasions of experience. We know in our own lives that some occasions are more valuable than others. Some are richer, more enjoyable, more meaningful. Even without a carefully articulated theory of value, we can make rough and realistic judgments that the subjectivity of the sea mammals is greater than that of fish, and that the subjectivity of a chimpanzee is greater than that of a chicken. Whitehead did work out a complex theory of value, but my point here is only to indicate that Whitehead's way of understanding human beings as part of nature both requires that we extend the ethical discussion and gives us clues as to how to do this.

When the sense of being part of nature is combined with the awareness of how all things are constituted by their relations with other things, the result is a powerful ecological vision. In my graduate school days I was not aware of the importance of this aspect of Whitehead's thought, although some of my teachers had understood this all along. Once the awareness of the ecological crisis broke through to me in 1969, the contribution of Whitehead to my self-understanding was greatly enriched. Responding to this crisis has been part of my central vocation ever since. To those who are seeking a new vision appropriate to our new situation, I strongly recommend that of Whitehead.

I will offer just one example of how this perspective helps. Among those who have genuinely overcome dualism in their thinking about humanity and the rest of the world, I find two major groups. These have arrived at their convictions through two quite different channels of thought. One group has become convinced that other animals suffer much as we do, and they are certain that our cruelty to them is immoral. The other group sees human beings as part of the interconnected web of life, and it sees value in the whole rather than in its isolated parts. If evaluations of individual creatures are made at all, it is in terms of their importance to the ecosystem. Often the most despised animals turn out to be indispensable.

The latter group regards the former as sentimental. As they see it, the ecosystem is indifferent to the suffering of individuals. Its greatness lies in the richness of life it generates and sustains through a process in which most individuals die young. The lesson to be learned is to stop imposing human moral values on nature and to live as part of the ecosystem in such a way that the whole flourishes.

Members of the former group have been hardly more charitable in their critique of the latter. How can one be sensitive to the whole of nature, they wonder, when one is indifferent to the individuals who make it up. We as human beings are inflicting levels of suffering quite disproportionate to those that characterize the wilderness ecosystem. We systematically torture hundreds of millions of animals in tests, and for instructional purposes, for only trivial gain to humanity. For the sake of slightly greater profit, we are transforming farms into factories in which many animals suffer horribly throughout their lives. Indifference to all this suffering is profoundly immoral, and if the ecosystem is not moral, that is no reasons for human beings to practice immorality, too. Advocates of animal rights, in their anger with this group of ecologists, have called them eco-fascists. With the number of those who have broken from anthropocentric thinking still so limited, it is discouraging and distressing that a good deal of their energy goes into fighting one another.

From a Whiteheadian point of view, both are correct in their affirmations, and these need to be formulated so as to complement one another. Value is located finally in the individual occasion, in this case, most significantly, in the individual occasion of animal experience. But that occasion is not a self-contained or self-enclosed entity. It is constituted by its relations to other things. Hence, while it is good to protect porpoises from tuna fishermen, it may be still more important to protect the ocean from poisoning, or from having its ecosystem so disrupted that whole species are destroyed. The wellbeing of individual animals is a function of the health of the ecosystem, and the ecosystem has value in and through the myriads of individuals that make it up. On the other hand, once we have removed animals from their natural habitat, and turned them into livestock and objects of experimentation, then the issue of their individual suffering comes to the fore.

V

Anthropology is so vast a field that I can certainly not exhaust it in one lecture. I am trying to be suggestive as to what a Whiteheadian perspective may contribute on a variety of topics. I will conclude with a more traditional theological one, the relation of divine grace and human freedom. My perception is that this discussion has been plagued by dualistic habits of mind, and that it can be advanced by applying Whitehead's radically nondualistic conceptuality.

The dualism to which I refer now is not that between human beings and other animals, but that between subject and object, or between a human experience and what acts upon it. Often the human being is seen as essentially self-enclosed and self-contained. It is supposed that one can describe what is taking place in the person without reference to God. It may be thought that God is the Creator of the person, so that the person would not exist at all apart from God. But as created, the person is seen as external to God, and God as external to the person.

With this imagery in place, a discussion of grace is begun. Since grace is the divine action upon the person, and since it affects the way the person is constituted, it has to be thought of as being somehow infused. God acts into the person's private domain. Of course, the action is for the person's good.

At this point questions arise. First, does the infusion occur in response to certain conditions being antecedently met by the person? Is it in some sense a reward for virtue? Or is the infusion decided upon by God, without reference to any merit on the part of the person? We all know that there are problems with both answers. The first leads toward moralism and the risk of self-righteousness. The second leads toward a view of divine arbitrariness that makes nonsense of human responsibility.

Second, when the infusion occurs, does it determine what happens or only create new opportunities? Is the person's cooperation required for grace to be effective, or is any apparent cooperation itself the work of grace, so that in fact the entire determination is in God's hands? These alternatives have the same dangers in this case as in the previous one.

From a Whiteheadian perspective, some of the problems arise because the initial picture is incorrect. If, instead, we picture the relation between God and the person as internal, the problematic is profoundly altered. To be a person at all is to be one whose very existence is partly constituted by the presence of God. It is this presence of God within the human occasion of experience, that makes the occasion something more than a deterministic outcome of the past. God's presence is the offering of relevant alternative ways of creatively responding to the past or to the total environment, as this also participates in constituting the new occasion. It involves the weighting of these alternatives, the call to realize some rather than others.

It is eminently appropriate to think of this divine presence in the occasion as grace. It is essential to the bare existence of the occasion, but it is much more than simply the ground of its being. It is liberating, empowering, creative, and redemptive. Sometimes it is prevenient, sometimes, justifying, sometimes, sanctifying. In every occasion, grace precedes human action as its necessary condition. In that sense, its priority is absolute. But that in no way reduces human freedom. The more effective grace is, the more genuine and significant is the self-determination that it makes possible and necessary. Furthermore, how effective grace can be in any moment, is affected by many things, but in particular by both the past working of grace and the personal response to that working.

If we think of matters in this way, there is little danger of being encouraged either in self-righteousness or in a sense of powerlessness before an all-determining God. Of myself, I am nothing; nothing, in the strictest sense. Furthermore, my very ability to decide is quite concretely God's gift, not simply in my original creation, but in the moment in which I decide. It is God who calls me to the best decision and empowers me. I may resist and fail to respond. But to whatever extent I do respond, it is by the grace of God. At the same time, my sense of the importance of rightly using the ever-renewed gift of freedom is heightened. How I respond shares in determining just what new gift God can give me. The more fully I respond, the more free God can make me. The more I open myself to God's grace the more I am a truly free person.

What is important here is to see the overcoming of another dualism. So often it appears that the more of what I become is determined by God, the less is determined by me in my freedom and responsibility. This means, the more grace, the less freedom, and the more freedom, the less grace. But when we understand the working of grace as I have proposed, then the relation is just the opposite. The more I am determined by God, the greater is my role in self-determination. To emphasize grace is to emphasize human freedom. To emphasize human freedom is to emphasize grace.

I am not proposing that this vision is unique to Whiteheadians. I find it, more of less consistently developed, both in the tradition and in more recent literature. My claim is only that Whitehead's conceptuality provides the most realistic and convincing grounds for thinking of grace in this way. I believe that can be an important contribution.

VI

You may have noticed that in the process of addressing anthropology I have talked of many other things, especially of God and the world. Something like this happens in Christian anthropology generally. The separation of one topic from others is always difficult for Christians. This difficulty is compounded for Whiteheadians. There is no human being apart from relations with other people, with other animals, and with the whole of creation. Certainly, there is no human being apart from God. To try to talk of what is human in separation from the rest of nature and God is to speak of an abstraction. Talk of abstractions is poor anthropology. I hope, therefore, that the very wandering of my lecture over a variety of topics will help you to understand the character of a Whiteheadian anthropology.